Anna MacDonaldI'm a biologist with interests in genetics, conservation, ecology, invasive species, and wildlife management. Archives

May 2019

Categories

All

|

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits I’ve used some of these photos in previous posts (here and here), but now I need to post an update. This little dragon is now known as the Monaro grassland earless dragon.

I’m excited to be a co-author on the paper, published last week in Royal Society Open Science (open access), that describes this species. This research combines several methods (phylogeography, phylogenomics, external morphology, micro X-ray CT scans) to review the grassland earless dragons of south-eastern Australia. It also shows how historic museum specimens can be important to understanding current biodiversity...

0 Comments

Read More

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits.

Anna I’ve selected three favourite papers from 2018: a research study, a think piece and a technical review. I was really excited to read “Digging mammals contribute to rhizosphere fungal community composition and seedling growth” (subscription) because I’m interested in how conservation management actions – in this case conservation and potential reintroduction of digging mammals – may have broader ecological impacts – in this case on ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity and fungal-plant interactions. Plus there are bandicoots involved. Best way to get my attention! The authors compared seedling growth and diversity of rhizosphere fungi in soil samples from inside and outside predator-proof sanctuaries (fenced reserves that protect digging mammals from introduced predators). They found that the presence of digging mammals was beneficial for growth of seedlings of a key forest tree species, and influenced ectomycorrhizal fungal community composition. Why is this important: digging mammals have declined dramatically all over Australia, and now we are starting to uncover the ecosystem services that have been lost with them… but that we may be able to restore....

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits.

I’m a fan of celebrating conservation success stories and sharing conservation optimism. In fact I’ve written about this before. Today, I want to share some wonderful teaching resources, that also highlight some reasons for hope in wildlife conservation. A little while back, I asked twitter to recommend short videos about mammal conservation in Australia, to include in lectures I was preparing. I wanted to illustrate some of the things that agencies need to think about when planning management strategies, and share some real examples of conservation actions with the students. Also, including videos of cute animals can make for a much more engaging lecture! Thanks to some lovely people I was sent links to a lot of interesting material. At the time I said I’d curate the list somewhere to make it easier for people to browse… and here it is. Please scroll down for links to a few videos about wildlife conservation, or with footage of threatened species. At this stage there is a strong focus on Australian mammals, but I’ll try to add links to other resources as I come across them. Feel free to share relevant resources with me… I know there are loads of other videos out there!

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits. When is a native species also invasive, and how can we tell? This may seem a strange question, but it highlights the difficulty we sometimes face determining the boundaries of the area in which a species naturally occurs. Especially when detection is imperfect and those boundaries may change over time. Animals move. Plants move. Sometimes a species will naturally move into a new area, and we recognise this as a range expansion. At other times, a species may only be able to move to a new area with human help (deliberate or unintentional), and this may create a new, invasive population. Think about Australia. If I asked you to name an invasive mammal, you might choose a fox, cat, rabbit or pig. These are clearly not native to Australia. What if I ask you to name a native mammal? Maybe you chose a red kangaroo or a wombat? They are both native to Australia, but they are not native to ALL of Australia. If we were to move a native species to a new part of the country where it had never previously occurred, it may not find the resources it needs to survive, but if it did, we may have created a new invasive population – an invasive native... Photo credit Dejan Stojanovic

Back to Blog

WildlifeSNPits post 04/03/2017: Marsupial misconceptions: weird mammals, placentas and pouches5/3/2017 Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits

I’ve now been living in Australia for almost 18 years, and I’m an unashamed convert to #TeamMarsupial. Marsupials are fascinating animals in both evolutionary and ecological terms, but at times I am surprised by how poorly-understood they are. I’ve been thinking of writing a post to address some recurring marsupial misconceptions for a while. When I saw how many marsupials were in the lineup for this year’s Mammal March Madness (more on this below) I decided that the time was right! So here we have it: eight things you might not know about marsupials, and profiles of the eight amazing marsupial species featured in Mammal March Madness 2017: Eight things about marsupials…

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSnpits

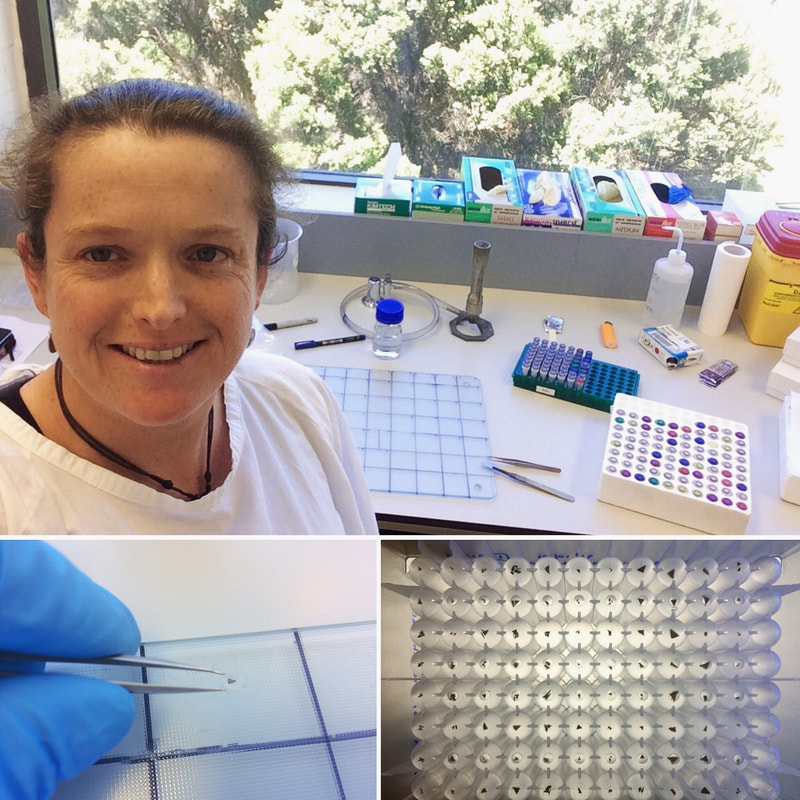

At this time last year I was quite uncomfortable about the idea of participating in #365scienceselfies, but still, I agreed to give it a go. I thought it was worth exploring as a different kind of science communication, to show what scientists look like and what we do. I never once thought I’d actually reach the nominal target of 365 selfies, but I was quite surprised to find that I shared 197 selfies during 2016. That’s more than I had expected. If you want to see them all in one place, I made a Storify of my #365scienceselfies posts. I was very consistent with posts during the first half of the year, only missing the occasional day, but there were more gaps between posts later on. In July and August I spent a few weeks in-between jobs, and a combination of travel and enforced vacation left me feeling less enthusiastic about taking science selfies. Subsequently I’ve been juggling a few different sets of responsibilities and found it a lot harder to remember to take photos when I was actually doing something interesting and sciencey. As a quick summary, of the 197 selfies I posted, 29 were taken in a lab and 50 with a computer. Sadly I didn’t really do any fieldwork this year, but I did include a few photos from hikes and bike rides. I took 36 selfies at meetings and talks (lab meetings, workshops, seminars, phone meetings…). Other people (colleagues, friends, family) featured in 45 photos and my dogs managed to “sneak” into 8 pictures. Strictly speaking, just under a third of my selfies didn’t actually feature me doing my job, although many of these were work-related, for example those taken at work functions. Finally, it won’t be a surprise to anyone who knows me to discover that 31 photos featured a cup of tea (or in a couple of cases, coffee)...

Back to Blog

WildlifeSNPits Post 17/12/2016: There’s no such thing as “boring” data in citizen science18/12/2016 Clink here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits

As a child I was hooked on wildlife documentaries (I still am…) and from these I gleaned that the career highlight of any self-respecting botanist or zoologist was to discover a new species. For a while that was my goal too, but then I became sidetracked by questions about genetics and evolution and conservation. Fast forward to the present, to the recent growth in citizen science, bioblitzes and nature apps, where almost anyone with an interest can find some way to contribute to scientific endeavour. I have experienced citizen science from both sides: as a scientist I have greatly appreciated the help of volunteers to collect samples and data; as a citizen I have contributed wildlife photos and sighting reports and helped with wildlife surveys and monitoring projects. All of the pictures I have shared in this post are ones I have recently uploaded to the Canberra Nature Map – I love taking wildlife photos and in addition to contributing to local biodiversity knowledge, the Canberra Nature Map is a great way for me to find out identifications for species I don’t know. There’s a lot of discussion among scientists at the moment about the effectiveness of citizen science, how to collect reliable data, and how to retain volunteers. Some of this surely comes down to the expectations and experiences of participants. One thing I’ve come to realise (through occasional conversations rather than proper data collection) is just how public perception of science can be skewed, and how this influences the idea of what “doing science” entails. Media fanfare tends to focus more on “big discoveries” in science – like the discovery of new species – and less on the years of routine, mundane, boring, data collection associated with those discoveries. I understand why that happens, but it can be misleading. Those who volunteer on conservation projects usually do so because they want to make a difference, so as scientists we need to make sure that people understand the many different ways in which they can make a difference...

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits

As many people know, two of my favourite topics are bandicoots and environmental DNA (eDNA). So I’m very excited about the online debut of my latest paper “A framework for developing and validating taxon-specific primers for specimen identification from environmental DNA” at Molecular Ecology Resources, which includes both bandicoots and eDNA. eDNA analysis is the analysis of DNA from environmental samples, which can include soil, water and animal faeces. eDNA studies can make valuable contributions to wildlife management, including management of invasive species, and conservation. Some animals are elusive, so relying on direct observations alone may not provide a true picture of where these species occur or which habitats they prefer to spend time in. eDNA detection, in conjunction with physical trapping, camera traps, and other survey data, has potential to improve our understanding of wildlife distributions. We may also want to learn about interactions between different species: predator-prey interactions are one example. This is where scat DNA is especially useful, as we can detect DNA from food remains in scats from a wide range of animals, including predators and herbivores. However… if we are going to use eDNA to guide management actions, which often require considerable investments of time and resources, we need to make sure that our eDNA studies are well-designed and reliable. Many eDNA tests use PCR and DNA sequencing methods to detect a single species or a group of closely-related species. These rely on the development of species-specific or taxon-specific PCR primers. We need to be confident that these primers will reproducibly detect the target species AND that they won’t also detect DNA from other wildlife that will be mistaken for the target species...

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits

I love going to scientific conferences. They provide me with great opportunities to learn about exciting new research, expand my professional network, and catch up with colleagues and old friends. Over the last few months (and at this point in previous years) I’ve spent some time evaluating student applications for a couple of different conference travel awards. Many academic societies offer such awards, providing grants to support and encourage undergraduate and / or postgraduate students to attend their annual conferences. This year I had more applications to read than usual, and found myself noting some of the same points (both good and bad) many times. So, while this is all fresh in my mind, here are my top five tips for writing a good travel award application*...

Back to Blog

Click here to read the full post at WildlifeSNPits

Bandicoots are fascinating creatures, but I suspect few people outside Australia and New Guinea have ever heard of them, well, unless you count Crash Bandicoot… They are probably best known in suburban Australia for infuriating gardeners with the conical pits, or “snout-pokes”, they dig whilst foraging for their food, which varies a little among species but usually includes fungi, plants and invertebrates. All Australian bandicoots are diggers, and a recent study estimated that a single southern brown bandicoot could dig as many as 45 foraging pits each day, meaning it has the potential to excavate around 3.9 tonnes of soil each year! That’s not bad for an animal that weighs less than 2 kilograms. In the not too distant past, bandicoots and their relatives could be found across almost the entire Australian continent, but theirs has been a sad story of extinction and decline since Europeans arrived. Today, thanks to habitat loss, competition from introduced rabbits, and predation by introduced cats and foxes (check out this camera trap photo, captured by Guy Ballard, of a feral cat with a bandicoot), many populations have diminished or disappeared. This may have real implications for the ecology of Australia: digging mammals seem to have important roles in soil turnover, water and nutrient cycling, and seedling recruitment, and the decline of these little diggers may have caused a deterioration in ecosystem function across the Australian continent. There is an awful lot more I could share about bandicoot ecology and evolution, but for now I want to concentrate on explaining what a bandicoot is, how many species there are, and where in the world they are found. I hope you’ll agree with me that as well as being amazingly cute (the official term is “bandicute”) they are also amazingly interesting... |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed